Competition for Water Resources

The competition for water supply is increasing throughout Florida. Increasing demands from residential and commercial users are often met at the expense of agricultural and environmental water supplies. As the number of Floridians continues to increase, water resources will decrease for agriculture. One way that citrus producers can address this trend is by reducing the amount of water consumed in commercial groves. Irrigation managers must reduce grove water consumption while avoiding tree damage or yield/fruit quality loss due to insufficient irrigation applications. The key to water management efficiency is to satisfy crop demands, addressing the various growth stages of the tree, and including both soil characteristics and weather into the decisions regarding irrigation.

Citrus Production Areas and Soil Characteristics

The production of citrus throughout Florida currently covers a large area within the peninsula. Because of the differences in soils and related water regimes, management techniques for irrigating commercial citrus groves must take these differences into consideration. For that reason, areas with similar soils and subsequently production practices are described below to make the discussion of irrigation and nutrient management more relevant.

Soils in the citrus production areas discussed below have been classified and mapped. This information can be found in the Natural Resource Conservation Service (NRCS) county soil survey maps (http://websoilsurvey.nrcs.usda.gov/app/). Soils are first classified based upon their Soil Order, which we shall use as the fundamental unit for irrigation management. Soil type is a further division of soils beyond soil order. Soils of the same type have very similar characteristics such as water and nutrient holding capacities. Soil types will be given as examples of soil orders present in the production areas described below. A more detailed description of the selected soil types are provided in SS403 "Common Soils Used for citrus Production in Florida" by T.A. Obreza and M.E. Collins (http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/SS403).

Ridge

The Florida Ridge (Figure 1) lies in a generally north and south direction through the center of the peninsula, and is characterized by deep, well drained soils comprised mostly of sand (Figure 2). The soil taxonomic order that dominates Ridge soils is the Entisols soil order.

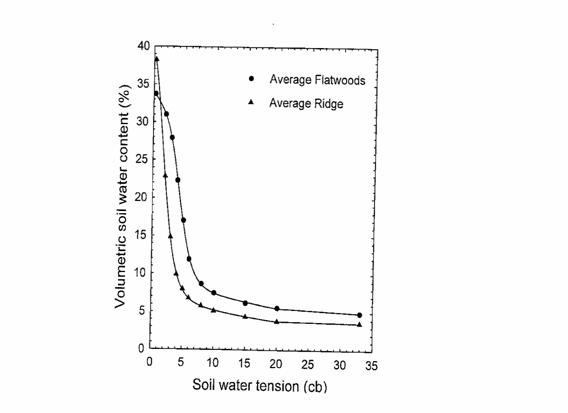

The so-called Flatwoods soils are found in both the Southwest Flatwoods ( Gulf Coast) and Eastern Flatwoods ( Indian River) citrus production areas (Figures 1 and 2). Because these soils are sandy, nutrient and water holding capacities are quite low. Many of these soils have a confining soil horizon that may permit a perched water table and negligible risk of nutrient leaching. Both the Indian River and the Gulf Coast production areas enjoy a somewhat reduced risk of nitrogen movement off-site, due in part to high water table conditions that are often present in these groves. Denitrification is the biological process of converting nitrate nitrogen into nitrogen gas by bacteria in water saturated soils. Thus, Flatwoods soils typically do not have water quality problems due to nitrate nitrogen. However, because drainage is required, water quality problems may be experienced in drainage waters/runoff from phosphorus and potassium. The soil taxonomic order that dominates Flatwoods soils are the Alfisols and Spodosols soil orders.

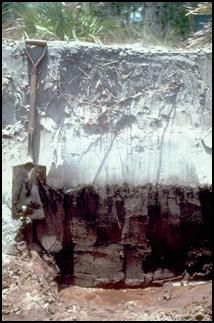

Another soil order commonly found in the Flatwoods and West Coast production areas are soils classified as Spodosols (Figure 6). Spodosols are poorly drained and exhibit a stained layer, known as the spodic horizon, within 1 to 3 feet of the soil surface. This horizon will support a perched water table; however, citrus roots do not readily grow within this diagnostic horizon primarily because of the elevated aluminum and iron concentrations present.

As with Alfisols, citrus production requires some form of drainage. Often the formation of beds provides acceptable moisture regime for a healthy root system.

Factors Affecting Irrigation Scheduling

As can be seen from the discussion of the citrus production areas within Florida, soil characteristics and soil type pose considerable restraints on irrigation practices.

Root Distribution

Irrigation decisions are affected by citrus root development and root patterns within the soil profile (shallow or deep).

Ridge: Entisols are often well-drained allowing citrus roots to penetrate deeply into the soil. This root distribution pattern anchors the tree and provides a large volume of soil from which the tree may extract both nutrients and water. Citrus root zones on Entisols are typically 36 inches or more in depth (Morgan et al., 2006).

Flatwoods: The drainage, the presence or absence of soil diagnostic horizons, and whether or not the citrus grove is bedded all have considerable influence on citrus root distribution (e.g., Figure 7). Because of drainage conditions, these soils are bedded for commercial citrus production, often with additional ditching to remove excess water. The shallow root system is restricted to the upper 12 to 18 inches of soil with approximately one third of the root system extending out to the edge of the bed. The remainder of the root system is located toward the center of the bed (Figure 7). A detailed description of root distribution in these soils can be found in HS146, "Some practical matters related to Riviera soil, depth to clay, water table, soil organic matter and Swingle Citrumelo root systems" by W.S. Castle, M. Bauer, B.J. Boman, and T.A. Obreza (http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/HS146).

Furthermore, depth to the water table influences the volume of soil that citrus roots can explore for both water and nutrients. Should the water table rise suddenly into the root zone, drainage must be applied (typically within six to 10 hours after flooding) or the affected roots will die. Root dieback due to a raised water table may adversely affect citrus fruit production as well as the health of the tree, possibly lowering resistance to pests or pathogens. In some groves with habitually high water tables, roots may occupy only the surface few inches of the soil resulting in trees that may not withstand wind from the ever present Florida thunderstorms (Figure 8). These groves are especially susceptible to hurricane wind damage.

Water Table

The location of a water table in the grove defines the lower limit of the volume of soil in which citrus roots can grow. When the water table is close to the surface the soil volume for root growth is decreased compared with a situation where the water table is several feet below the soil surface or the bed top. Thus, the first step in developing good irrigation practice within the grove is to know the depth to the water table using some form of monitoring (see list of EDIS publications below).

CIR1408/CH151, "Water Table Measurement and Monitoring for Flatwood Citrus" by B.J. Boman and T.A. Obreza (http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/CH151).

CIR731/AE130, "Manual Monitoring of Farm Water Tables" by , (http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/AE130).

If the water table is close to the soil surface or bed top, it stands to reason that irrigation volume should be reduced. Correctly managing the volume of water in each irrigation cycle has a strong effect on roots and their proper development, leading to a healthy and productive citrus tree. In recent research, the root to shoot ratio was changed dramatically when the root volume was restricted due to high water table and/or excessive irrigation. Trees with expanded canopy volume, and therefore with potential for higher commercial fruit production, require increased root to shoot ratios. In situations where roots have been damaged, either by inappropriate irrigation or by a flooding event, the reestablishment of the root to shoot ratio should be attempted as soon as possible. In cases where damaged roots are extensive, managers should establish appropriate drainage to provide a soil volume into which roots may recover and grow. In more drastic situations, managers should consider canopy pruning to match the canopy volume with the recovering root system.

Drainage

Flatwood soils are often poorly drained and relatively easily flooded. For citrus production, some form of drainage or surface relief must be provided. Adequate soil drainage must be maintained for proper tree growth and root system development. Many EDIS publications have been produced describing proper drainage system design, maintenance, and management (see list of EDIS publications below).

CIR1405/AE216, "Detention/Retention for Citrus Storm Water Management" by B.J. Boman, C. Wilson, M. Jennings, and S. Shukla (http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/AE216).

CIR196/SS459, Flatwood Citrus Best management Practice: Riser-Board Structures" by C. Wilson, L. Scotto, B.J. Boman, and J. Hebb (http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/SS459).

CIR1412/CH165, "Drainage Systems for Flatwood Citrus in Florida" by B.J. Boman and D.P.H. Tucker (http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/CH165).

CIR1419/CH163, "Water and Environmental Considerations for the Design and Development of Citrus Groves" by B.J. Boman, N. Morris, and M. Wade (http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/CH163).

Irrigation Depth and Duration

Irrigation duration and flow rate determine the volume of water that is added to the grove. Gravitational forces move the water downward through the soil until the soil has reached field capacity. Any additional irrigation water either continues through the soil profile below the root zone, or reaches the water table, in both cases water above the amount required to refill the soil in the root zone is wasted and potentially contributes to nutrient leaching.

Soil characteristics also pose problems for irrigation and nutrient management. Scheduling must be such that irrigation avoids exacerbating loss of nutrients, especially nitrogen, from the citrus root zone. Scheduling decisions are further confounded by rainfall. For example, irrigation just before a rain event wastes both the irrigation water and likely some fertilizer-supplied nutrition, since the rain fills the surface soil causing nutrient filled water to be pushed past the rooting zone, leaching nutrients from these well-drained, sandy soils. This simplified model of water movement has been called "piston flow" because water entering the soil from irrigation or rainfall forces water in the soil deeper into the soil profile. This very much describes the flow of nutrients in the well drained sandy soils of central and south Florida, making them vulnerable to nutrient leaching.

The wetted portion of the soil profile can be controlled by irrigation managers. If the volume of irrigation water is excessive, then this over-watering can induce the same problems discussed above concerning drainage and excess water from rainfall. The goal of the irrigation program should be to supply water needed by the citrus tree in a timely manner and to avoid wetting additional soil or moving water below the root zone.

Depth of Water Infiltration and Depth of Soil at Field Capacity

A good way to know if the irrigation water is being used correctly, avoiding too wet or too dry conditions, is to estimate the depth of wetting and the total depth of soil that will be filled to Field Capacity. A simple estimate can be generated using easily available information and making some assumptions. The estimate is described in more detail in Appendix 1, and is used in the following examples. More powerful estimation methods have and are being made available. For example, one estimation model is available through the FAWN weather system (fawn.ifas.ufl.edu/citrus irrigation scheduler), a web-based weather reporting system for agricultural uses.

From Appendix 1, Table 1, the Candler soil will wet to field capacity to a depth of approximately 22 inches, given the original soil-water content in the example equivalent to 1/3 depletion, and the addition of 1 inch of irrigation water. Of course, a wetter soil at the beginning of the irrigation cycle would result in soil being brought to Field Capacity to a greater depth. Based upon grove rooting depths, the implication is that much more than a 1-inch water application may extend Field Capacity conditions below the rooting depth of the citrus trees in a Candler sand. Please see Appendix 1 for another example using a different soil.

Goals of Irrigation Scheduling

A grove manager may have several objectives for using irrigation. The priority listing of these objectives by the grower will allow the grower to give emphasis to selected objectives and reflect that emphasis in the irrigation strategies. The following list of objectives, though not exhaustive, contains some typical reasons for the use of irrigation. Profits through the effective use of resources to produce high quality citrus in commercially viable quantities encapsulate the overall goal. The economics driving these priorities are left to the individual operator; however, this publication provides some decision-making information regarding irrigation use, scheduling, and duration.

Maximum yield per acre: While many producers state this objective, research has shown that maximum yields are not the most cost-effective to achieve, and often contribute to off-grove pollution. Environmental impact is due to increased fertilizer applications to counter balance the excessive irrigation required for maximum production resulting in reduced nutrient use efficiency.

Maximum yield per amount of water applied (water use efficiency): This objective requires good control of water delivered to the tree, and results in conservation of water, as well as the energy used to move water from its source to the tree. In this case, both the delivery system to get the irrigation water to the tree and the tree response are considered.

Maximum yield per unit of fuel (fuel efficiency): Similar to the objective above, fuel or energy is the focal point. With rising fuel costs, this objective addresses water consumption from the standpoint that the conveyance of water to the tree takes energy, which requires a system that is energy efficient. Maximum nutrient uptake (nutrient use efficiency site: Linking citrus irrigation management to citrus fertilizer practices): As water moves into the tree, selected nutrients (e.g., nitrate-nitrogen) move with the water and enter the tree. Nutrient use increases if the correct amount of both nutrient and water are used, resulting in increased nutrient-use efficiency. Because nutrients are also energy-intensive, this objective integrates management of nutrients, water, and energy. Irrigation practices to improve nutrient use efficiency are given in CIR####/SS###, "Improving nutrient uptake efficiency:Liking citrus irrigation management to citrus fertilizer practices" by K.T. Morgan and E.A. Hanlon (http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/SS###).

Minimize nutrient leaching: This objective attempts to hold nutrients, especially the mobile nutrients, such as nitrate nitrogen, in the root zone via measured irrigation events. Irrigation timing and duration are based upon crop need and soil-moisture content. In addition to addressing plant water needs, the soil volume comprising the root zone is also included, as well as rainfall events to the extent possible.

Irrigation Scheduling

The following are the methods of irrigation scheduling that will improve the likelihood of obtaining the irrigation goals above.

Tables

Generic irrigation schedules can be reduced to a tabular format, as described in HS958/HS204, "Management of Microsprinkler Systems for Florida Citrus" by L.R. Parsons and K.T. Morgan (http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/HS204). All of the information required to produce a table similar to Table 5 can be found in reference materials such as the county soil survey, measurement of rooting depth in each of the groves, and following UF/IFAS guidelines for soil-water depletion percentages.

Water Budget Approach

When water is lost from the soil by evaporation and the citrus tree losses water through the transpiration process, water must be supplied to replace this crop evapotranspiration (ETc). A so-called reference evapotranspiration factor (ET0, Figure 9) can be used as a basis for estimating the evapotranspiration component of the total irrigation demand. Reference ET is calculated on a daily basis using weather data or is available for the nearest FAWN site as (https://fawn.ifas.ufl.edu). The calculation of reference evapotranspiration using weather data is described in HS950/HS179, "Weather Data for Citrus Irrigation Management" by L.R. Parsons, and H.W. Beck (http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/HS2179).

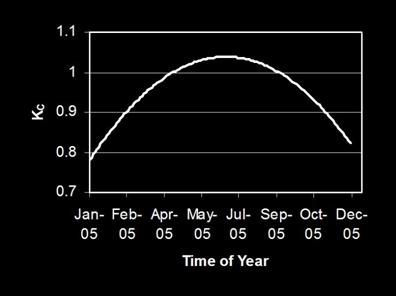

Two factors must be used to convert the reference ET to one that addresses citrus growing in specific soils found in the grove of interest. The crop coefficient (Kc) for citrus changes throughout the year (Figure 10) and is low during the cooler months when water use is low and higher in the warm summer months when water use by the citrus trees are high. The soil-water extraction factor (Ks) is an estimate of the ability to supply water throughout a range of water contents (Figure 11).

The equation: ETc = ETo*Kc*Ks uses these components to estimate the crop ET. However, once the crop ET is estimated, another simple set of calculations can be used to predict when irrigation should occur. This method utilizes current soil-water information and the ETc in a simple water budget:

Current Soil-water=Yesterday's Soil-water-ETc.

Detailed discussion of crop ET is available in BUL249/AE111, "Basic Irrigation Scheduling in Florida" by A.G. Smajstrla, B.J. Boman, D.Z. Haman, F.T. Izumo, D.J. Pitts, and F.S. Zazueta (http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/AE111) and BUL254/AE118, "Irrigation Scheduling with Evaporative Pans" by A.G. Smajstrla, F.S. Zazueta, G.A. Clark, and D.J. Pittts (http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/AE118).

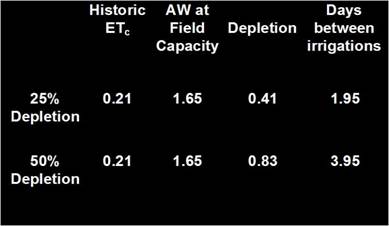

A decision should be made before using this equation. That is, what amount of depletion of the soil's available water should be used before irrigating? The UF/IFAS recommendation is to allow 25 to 33 percent soil-water depletion during February through May, and 50 to 66 percent depletion during June through January. The examples (Table 3) show the use of 25 and 50 percent soil-water depletion, one from each of recommended time periods.

Rooting depth adds another layer of precision to this irrigation budget model (Table 4). Notice that the time between irrigation events is longer as the rooting depth increases. So long as roots are actually present within the entire volume, the plant has considerably more soil volume from which to draw water. Overestimating the actual rooting depth is ill advised, wasting water and possible loss of nutrients below the root zone.

Note also that the ET changes during the year, also affecting the time between irrigation events, as well as the irrigation duration. Lastly, notice that an increase in the allowable depletion (going from 25% to 50%) also increases both the time interval and the duration of irrigation events.

Soil Water Measurement Approach

The direct measurement of soil water has been used for irrigation scheduling for many decades. Recent advances in soil water sensor technology and the proliferation of computers in production agriculture has made using these devices easier and more common place. The simplest device is the tensiometers, which measures the force or tension that water is held to the soil. As soils dry, the water remaining in the soil is held more tightly by the soil and is thus, less available to the tree. This is particularly true of the sandy soils in Florida, and is the major consideration for the maximum level of soil water depletion allowed prior to irrigation. The soil can not be allowed to dry too much or the plant stress will increase affecting growth and yield. Discussion or the installation, maintenance and use of these devices are described in CIR487/AE146, "Tensiometers for Soil Moisture Measurement and Irrigation Scheduling by A.G. Smajstrla and D.S. Harrison (http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/AE146).

A wide range of electronic sensors are available to citrus growers for measurement of soil water content or tension. These sensors are typically more expensive that the simple tensiometer but have the advantages of high accuracy, low maintenance, and most will connect directly to computers or irrigation controllers for data collection. These sensors are described in BUL343/AE266, "Field Devices for Monitoring Soil Water Content" by R. Munoz-Carpena (http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/AE266).

For More Information …

Alva, A.K., and S. Paramasivam. 1998. Nitrogen management for high yield and quality of citrus in sandy soils. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 62:1335-1342.

2002. Water and Environmental Considerations for the Design and Development of Citrus Groves in Florida. http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/CH163 . Accessed 14 July, 2006.

2002 Drainage Systems for Flatwoods Citrus in Florida. http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/CH165 . Accessed 14 July, 2006.

Water Table Measurement and Monitoring for Flatwoods Citrus. http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/CH151 . Accessed 14 July, 2006.

McPherson, B.F., Miller, R.L., Haag, K.H., and Bradner, Anne. 2000. Water Quality in Southern Florida Florida,1996-98: U.S. Geological Survey Circular 1207, 32 p., on-line at https://pubs.usgs.gov/circ/circ1207/

Morgan, K.T., and E.A. Hanlon. 2006. Annual citrus nitrogen requirements. http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/SS459 . Accessed 14 July, 2006.

Morgan, K.T., T.A. Obreza, J.M.S. Scholberg, L.R. Parsons, and T.A. Wheaton. 2006. Citrus water uptake dynamics on a sandy Florida Entisol. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 70(1):90-97.

Morgan, K.T., J.M.S. Scholberg, T.A. Obreza, and T.A. Wheaton. 2006. Size biomass, and nitrogen relationships with sweet orange tree growth. J. Am. Soc. Hort. Sci. 131(1):149-156.

Field Devices for Monitoring Soil Water Content. http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/AE266 . Accessed 14 July, 2006.

Natural Resource Conservation Service (NRCS) county soil survey maps (http://websoilsurvey.nrcs.usda.gov/app/ ).

Obreza, T.A., R. Rouse, and E.A. Hanlon. (in press). Advancements with Controlled-Release Fertilizers for Florida Citrus Production: 1996 -2006. EDIS.

Obreza, T. A. 1993. Program fertilization for establishment of orange trees. J. Prod. Agr. 6:546-552.

2003. Prioritizing Citrus Nutrient Management Decisions. http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/SS418 . Accessed 14 July, 2006.

Obreza, T.A., D.J. Pitts, L.R. Parsons, T.A. Wheaton, and K.T. Morgan. 1997. Soil water-holding characteristic affects citrus irrigation scheduling strategy. Proc. Fla. State Hort. Soc. 110:36-39.

Common Soils Used for Citrus Production in Florida. http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/SS403 . Accessed 14 July, 2006.

Citrus Grove Leaf Tissue and Soil Testing: Sampling, Analysis, and Interpretation. http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/CH046 . Accessed 14 July, 2006.

Paramasivam, S., A.K. Alva, A. Fares, and K. S. Sajwan. 2001. Estimation of nitrate leaching in an Entisol under optimum citrus production. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 65:914-921.

2004. Weather Data for Citrus Irrigation Management. http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/HS179 . Accessed 14 July, 2006.

2004. Management of Microsprinkler Systems for Florida Citrus. http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/HS204 . Accessed 14 July, 2006.

Smajstrla, A.G., B.J. Boman, G.A. Clark, D.Z. Haman, D.S. Harrison, F.T. Izuno, D.J. Pitts and F.S. Zazueta. 2002. Efficiencies of Florida Agricultural Irrigation Systems. http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/AE110 . Accessed 14 July, 2006.

2000. Irrigation Scheduling with Evaporation Pans. http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/AE118 . Accessed 14 July, 2006.

Zazueta. Basic Irrigation Scheduling in Florida. http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/AE111 . Accessed 14 July, 2006.

2003. Irrigation, Nutrition, and Citrus Fruit Quality. http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/SS426 . Accessed 14 July, 2006.

Increasing Efficiency and Reducing Costs of Citrus Nutritional Programs. http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/SS442 . Accessed 14 July, 2006.

Table 1. Example of an irrigation schedule using the following assumptions: field capacity equals 0.08 to 0.10 in/in; rooting depth equals 18 inches; irrigation application rate equals 0.1 to 0.15 in/hr; allowable soil-water depletion was set at 25% during the spring and 50% during the summer and winter. (Source: http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/HS204 )

Jan. |

Feb. |

Mar. |

Apr. |

May |

Jun. |

Jul. |

Aug. |

Sept |

Oct. |

Nov. |

Dec. |

|

ET (in/day) |

0.07 |

0.11 |

0.13 |

0.18 |

0.20 |

0.21 |

0.20 |

0.19 |

0.16 |

0.12 |

0.09 |

0.06 |

Interval (days) |

7-10 |

3-4 |

3-4 |

2-3 |

2-3 |

2-3 |

3-4 |

3-4 |

3-5 |

4-6 |

5-8 |

7-10 |

Duration (hours) |

5-6 |

3-4 |

3-4 |

3-5 |

4-5 |

4-5 |

4-6 |

4-6 |

4-6 |

4-6 |

4-6 |

4-6 |

Table 2. Using crop ET and selected soil-water depletion levels to estimate days between irrigation events. ETc is the crop ET, AW is soil-available water at field capacity. Depletion is the percentage of AW desired between irrigation events.

Table 3. Three selected routing depths, estimated available soil water, and resulting irrigation schedule (time between each irrigation event in days; irrigation operation time in hours).

Rooting Depth==> |

12 in. depth |

18 in. depth |

24 in. depth |

Field Capacity (in/in) |

0.09 |

0.09 |

0.09 |

Available Soil Water (in) |

|||

Feb. - June. (25%) |

0.27 |

0.41 |

0.54 |

July- Jan. (50%) |

0.54 |

0.81 |

1.08 |

Irrigation Schedule |

|||

Jan. (ET= 0.08) |

6-7 days |

10-11 days |

13-14 days |

3-4 hours |

5-6 hours |

7-8 hours |

|

May (ET=0.20) |

1-2 days |

2-3 days |

2-3 days |

1-2 hours |

2-3 hours |

3-4 hours |

|

August (ET=0.22) |

2-3 days |

3-4 days |

4-5 days |

3-4 hours |

5-6 hours |

7-8 hours |

|

Figure 1. Florida citrus production areas

by county.

Figure 1. Florida citrus production areas

by county.

Figure 2. Soils in citrus production areas of Florida (Obreza et al., 2006)

Figure 3. Entisols: Candler fine sand (Entisols) is a typical Ridge soil. Notice that there are no discernible diagnostic horizons throughout the soil profile. The darker gray color at the soil surface is caused by the addition of organic matter from plant growth.

Figure 4. Average soil-water characteristic curves representing Flatwoods (Spodosols) and Ridge (Entisols) soil from the root zone (Obreza et al., 1997). Note that Flatwoods soils contain somewhat more plant-available water than the Ridge soils.

![]()

Figure 5. This Alfisol, a Riviera sand, shows the typical diagnostic horizons. The build up of the clay layer in the lower one third of the profile is quite evident.

Figure 6. This Immokalee fine sand has the typical profile of a Spodosol. Note the dark stained layer, the spodic horizon, in the

lower portion of the picture caused by a buildup of iron, aluminum, and organic

matter.

Figure 7. Citrus root growth in a Riviera sand, an Alfisol, is mostly in the surface few inches (Rootstock and Soil

Interactions Project, Bauer, Castle, Boman, and Obreza)

Figure 8. Roots of citrus trees with shallow and weak system on the left, and a normal strong root system on the right.

Add Later

Figure 9. Reference Evapotranspiration (ETo)

Figure 10. Crop coefficient (Kc) for citrus.

Figure 11. Soil-water extraction factor.